Refusing to Be Shut Out: Archibald Alphonso Alexander

By R. Kofi Bempong

Archie Alexander defied racial barriers to become a pioneering engineer, building bridges, highways, and airfields across America. From Iowa to Washington, D.C., and the Tuskegee Airmen’s airfield, his work shaped infrastructure and history.

The first morning after Archie Alexander moved into his new home—a stately house in an upscale white neighborhood in Des Moines—he woke up to the sight of a burning cross on his front lawn. It was 1944, and despite being one of the most successful engineers in the country, despite his company having built bridges, highways, and military airfields across America, there were still those who thought they could dictate where he did or didn’t belong. They were wrong.

Standing well over six feet tall with the powerful build of a former football player, Alexander wasn’t the kind of man to be intimidated. He had spent his entire life walking into rooms he wasn’t wanted—classrooms, boardrooms, construction sites—and leaving with contracts in hand. His life was shaped by self-reliance, acute strategic thinking, and a refusal to accept rejection.

From Small-Town Iowa to Mega Engineering

Born in 1888 in Ottumwa, Iowa, Mr. Alexander grew up in a small Black community—fewer than 500 people in a town of 14,000. His father, Price Alexander, rose from being a coachman to serving as head custodian at the Des Moines National Bank, a position rarely held by a Black man. The family later moved to a farm outside Des Moines, where young Archie’s fascination with construction began. One of his favorite childhood pastimes was building dams in a local creek.

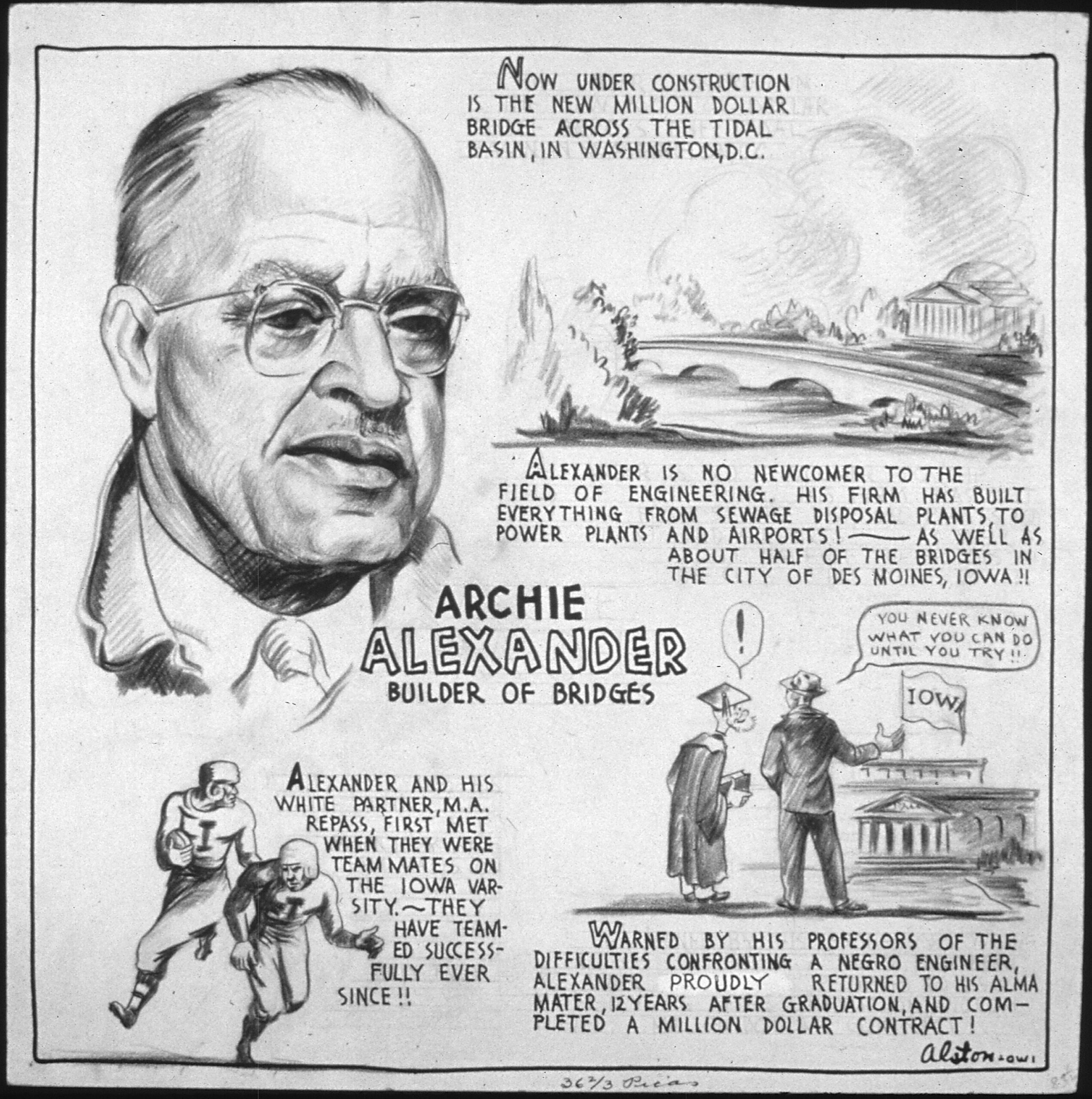

That childhood fascination became a serious pursuit when he enrolled at the State University of Iowa (now the University of Iowa) to study engineering. There, a professor bluntly told him that “engineering is a tough field at best, and it may be twice as tough for a Negro” and revealed that he had “never heard of a Negro engineer.” Instead of being discouraged, Alexander thrived. He became the university’s first Black engineering student and its first Black football player, earning the nickname “Alexander the Great” for his commanding presence on the field.

He graduated in 1912 with a civil engineering degree, but even with his education and experience working as a draftsman, no engineering firm in Des Moines would hire him.

Building a Path Forward

Alexander started where he could—working as a low-paid steel shop laborer. However, within two years, he oversaw bridge construction projects in Iowa and Minnesota. In 1914, he leaped and founded his firm, A.A. Alexander, Inc.

His first major business decision was a strategic one. Recognizing that contracts from Black clients alone wouldn’t sustain his firm, he partnered with a white contractor, George F. Higbee, in 1917—their firm, Alexander & Higbee, specialized in bridges, sewer systems, and road construction. The partnership lasted until Higbee died in 1925.

Shortly after, he landed one of his most significant contracts—the $1.2 million central heating and generating station for the University of Iowa in 1927, a facility that still operates today. He continued working for his alma mater, constructing a power plant and an underground tunnel beneath the Iowa River to connect different parts of the campus.

In 1929, he teamed up with a fellow University of Iowa football alumnus, Maurice A. Repass, forming the firm Alexander & Repass. The Great Depression nearly crushed them. At one point, they laid off all their workers and took on small repair jobs to survive. But a strategic partnership with contractor Glen C. Herrick helped them regain financial stability, leading to more large-scale projects. Among them were a million-dollar sewage treatment plant in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Nebraska’s Loup River Power Plant.

During World War II, Mr. Alexander’s firm won high-profile government assignments, including constructing an airfield for the 99th Pursuit Squadron in Alabama, the famed Tuskegee Airmen’s training ground.

Shaping the Nation’s Capital

Washington, D.C., soon became a major focus of Mr. Alexander’s work. His firm took on projects that reshaped how people moved around the city, from the Tidal Basin Bridge and Seawall to the K Street elevated highway and underpass. He also played a significant role in creating the Whitehurst Freeway, a $3.5 million project that guided traffic around Georgetown. He was responsible for an overpass on Riggs Road beneath the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

1955, he turned his attention to housing, developing the Frederick Douglass Memorial Estate Apartments in Anacostia, Washington D.C.

Engineering, Architecture, and Business Acumen

Although Alexander was primarily known as an engineer, he was often referred to as an architectural engineer—a term reflecting his involvement in design and construction. His firm’s work on infrastructure projects—usually blending engineering precision with architectural elements—cemented his reputation in both fields.

Yet, Alexander wasn’t just a builder of structures but also a master strategist. His ability to secure contracts in an industry that largely excluded Black professionals was a feat in itself. “Some of them act as though they want to bar me, but I walk in, throw my cards down, and I’m in,” he once said. “My money talks—just as loudly as theirs.”

A Turn to Politics—and a Bitter End

Alexander’s success in business led him to political prominence. He served as a trustee for Tuskegee Institute and Howard University, chaired numerous race relations committees, and was an active member of the Republican Party. In 1954President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The appointment, however, turned sour. Alexander’s blunt, no-nonsense leadership style clashed with the island’s local legislators. He pushed for aggressive development, but his business ties in the Caribbean led to accusations of cronyism. Under mounting political pressure and declining health, he resigned after 18 months.

The Final Years

After leaving politics, Alexander returned to Des Moines, where he lived quietly until his death from a heart attack in 1958. Though his time as governor was rocky, his impact as an engineer and businessman was undeniable.

The bridges he built still stand. The roads and power plants he constructed still serve communities. And the firm he founded, against all odds, is evidence of his vision and resilience. Whether confronting a cross set aflame on his lawn or boards that preferred to lock him out of meetings, Archie Alexander simply built a new way forward.