Los Angeles

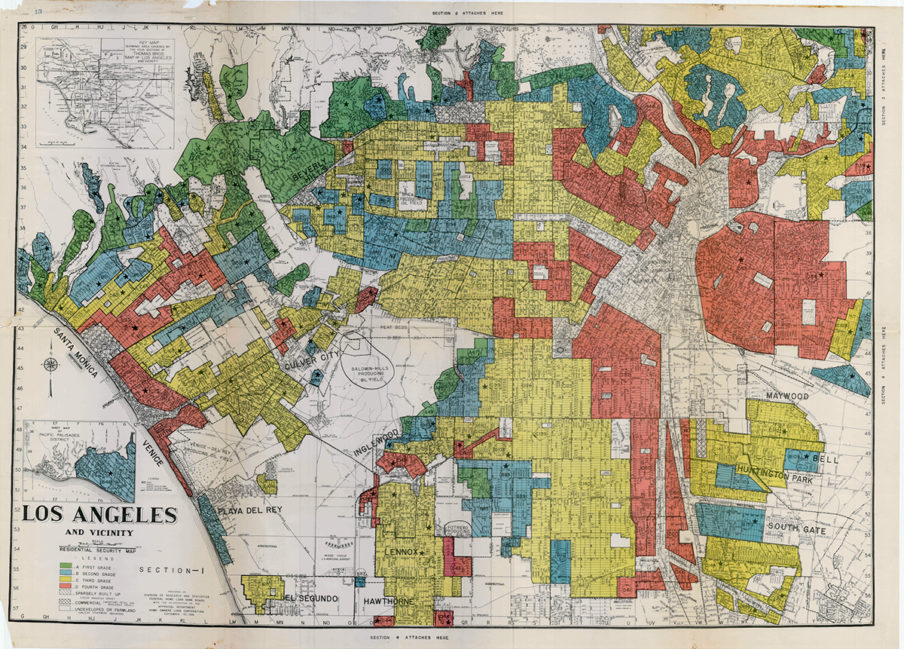

However, beginning with the uptick in the 1930s of migration of both whites and African-Americans from Southern states to Los Angeles, segregation became increasingly ensconced in city policy and the social geography of Southern California. Between 1930 and 1950, the number of African-Americans living in Los Angeles increased from 30,893 to 200,000 and with the increased number of African-Americans, many of whom came to Los Angeles with less wealth than the middle-class African-Americans who had long lived in the city, a new era of racist housing policy began to take root. Real estate agents, lawyers, and white homeowners alarmed by the appearance of black neighbors, began to devise exclusionary covenants that precluded African-American home ownership in the same predominately middle-class neighborhoods where many black Angelenos had long resided. Meanwhile, many white residents began to move outside the city to the San Fernando Valley where Federal Housing Authority policy had made it impossible for African-Americans to receive insured mortgages under the technique known as “redlining.” Despite the Supreme Court’s 1948 decision outlawing restrictive housing covenants, a case that was precipitated by events that took place in Los Angeles during the 1930s, the durability of segregationist attitudes towards housing lasted well into the second half of the twentieth-century.

Central Avenue, the historic center of Los Angeles’s African-American communities.

More recently, Los Angeles has played host to a disjunctive series of events that simultaneously point to the lasting legacy of the racist structuring of urban space. Almost twenty years after Los Angeles elected the first black mayor in the entire country, a former police officer, Tom Bradley, the urban grid of South Central Los Angeles became ensnarled by violence following the acquittal of the four police officers who were videotaped beating Rodney King. The relation between urban space and the communities that have settled in Los Angeles at various points in the African diaspora resists any single progressive narrative, instead amounting to an unending accumulation of significant architectural sites, innovations in urban design, and culturally enriching interventions in the landscape.

Paul Revere Williams illustration

Despite the multiplicity of stories that characterize black design in Los Angeles, the city’s built environment has been indelibly shaped by the groundbreaking accomplishments of African-American designers. Paul Revere Williams (1894-1980), the most well-known African-American architect from Los Angeles, tactfully navigated both the elite social networks of the city and the everyday racism that constantly confronted his work. Most famously, Williams is noted for his work on the Los Angeles Jet Age Terminal Construction project that reshaped the Los Angeles International Airport led to the construction of the iconic Theme Building. Fluidly mastering the architectural paradigm of the academy as well as vernacular regional styles, Williams seamlessly worked across such disparate formal languages as Spanish Revival and Moderne, leaving behind a voluminous catalog of built homes occupied by many of the mid-century entertainment industry’s august personalities. The architectural significance of Los Angeles was further enriched by the contributions of Norma Sklarek (1926-2012), the first African-American woman to become a member of the AIA. A graduate of Barnard College and Columbia University’s architecture department, Sklarek moved to Los Angeles to become a director at Gruen before opening her own firm in 1980 which would become the country’s largest woman-owned architectural office. Sklarek is known for the exuberant yet constrained postmodernism of the Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo.

Norma Sklarek

Sources

Quoted in Rudolph Lapp, Afro-Americans in California (San Francisco: Boyd & Fraser, 1987), 39.

Susan Anderson, “A City Called Heaven: Black Enchantment and Despair in Los Angeles,” 336-364, in The City: Los Angeles and Urban Theory at the End of the Twentieth Century, Allen J. Scott and Edward W. Soja, eds. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996), 340. Ibid., 341. Ibid, 344. Ibid., 345.