John Louis Wilson Jr.

Shortly after starting his own practice in 1933 on 125th Street, Mississippi-born Wilson was recruited as the only Black architect on a team of six to design the Harlem River Houses, the nation’s first federally financed housing project. The development’s history reflects both the promise and disappointments of public housing in the United States, but also key aspects of Black communities’ place in Depression-era New York and how persistent racial discrimination and assumptions sullied then-progressive government-led housing efforts. It was the first project in a broader FDR-led housing construction campaign during the Great Depression aimed at addressing dire housing conditions in several cities, as well ameliorating broader economic hardship, high unemployment, and social dislocation. Though Harlem was already a flourishing, economically and socially diverse Black community, it suffered from a severe undersupply of adequate housing, due to discriminatory lending practices, redlining, and structural discrimination, all made worse by the economic downturn. What housing did exist was often substandard and overcrowded, in conditions comparable to the largely immigrant neighborhoods in the Lower East Side downtown. “Harlem needs good housing,” a 1937 brochure from the Public Works Administration plainly stated.

Sculpture in the courtyard of the Harlem River Houses' block at the W. 151st Street entrance by James Richmond Barthé & Heinz Warneke

Christina E. Crawford, licensed under Creative Commons

West block entrance at W. 152nd Street and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard

Christina E. Crawford, licensed under Creative Commons

The national economic context coupled with local political developments, such as the establishment of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) in 1934, heralded a public housing boom in the city, and the Harlem River Houses was the first to open in 1937. The red-brick complex is a humble, Modernist experimentation in housing, comprising seven hunkered volumes facing a patchwork of gardens, plazas, and courtyards, many of which were enlivened with murals and sculpture. The interweaving of public and indoor space was aimed at facilitating functional connections within and between households: keeping an eye on playing children, for example, or encountering neighbors while traversing the complex. About two-thirds of the site is given over to open spaces, and the original facility had community functions like health and child care on site. The project’s spatial relationship to its surroundings was also sensitive and socially minded, with ample street connections, well maintained passageways, and a contextually deferential but subtly elevated material palette. The results, which Wilson had called “humane living,” helped form a basis of the garden apartment typology and are a far cry from the stigma attached to public housing today.

A courtyard and sunken playground at the Harlem River Houses

Christina E. Crawford, licensed under Creative Commons

But despite the lofty intentions of the 1930s building campaign in general, and of the Harlem River Houses in particular, several qualifications show that the projects were still shaped by systems of racial hierarchy of the time. Wilson allegedly fought hard to secure bathtubs for the community’s residents, which his white colleagues wanted to scrap due to budgetary constraints. On a larger scale, segregation was not only still societally predominant, but explicitly advanced by government agencies, with the Harlem River Houses expressly created for Black residents and its sister project, the Williamsburg Houses in Brooklyn, for whites. Large-scale residential developments also supplanted hundreds of smaller houses, interrupting finer-grain, long-standing neighborhood fabrics. Wilson’s projects, then – from Harlem in the 1930s to projects such as Stuy Park House in Crown Heights in 1975 – were tied up in the fundamental quandaries and paradoxes of urban renewal that continue to be debated today. But most practically, however, the Harlem River Houses was fundamentally insufficient in meeting local housing needs: For 574 available apartments were 11,000 applicants. Such constraints speak to the essential limitations of the architect, especially a Black architect who sought to advocate for his community while operating within a white-dominated profession and engaging with white-dominated government agencies and programs.

Wilson succeeded in building other civic-minded, forward-looking structures for diverse, working class communities around New York – including the Throgs Neck Public Library in the Bronx and the Boys and Girls High School in Bed Stuy – but like all good architects, his impact is most evident in the social connections and progress his work, both built and unbuilt, enabled. Wilson cofounded the Council for Advancement of Negroes in Architecture in the 1950s; after it was subsumed by the AIA in the ‘60s, he served as chairman of its Equal Opportunities Committee. A 1980 exhibition on his work at Columbia GSAPP organized by the New York chapter of NOMA testifies to his enduring presence in architectural education, particularly in New York, where he lived and worked until his death in 1989.

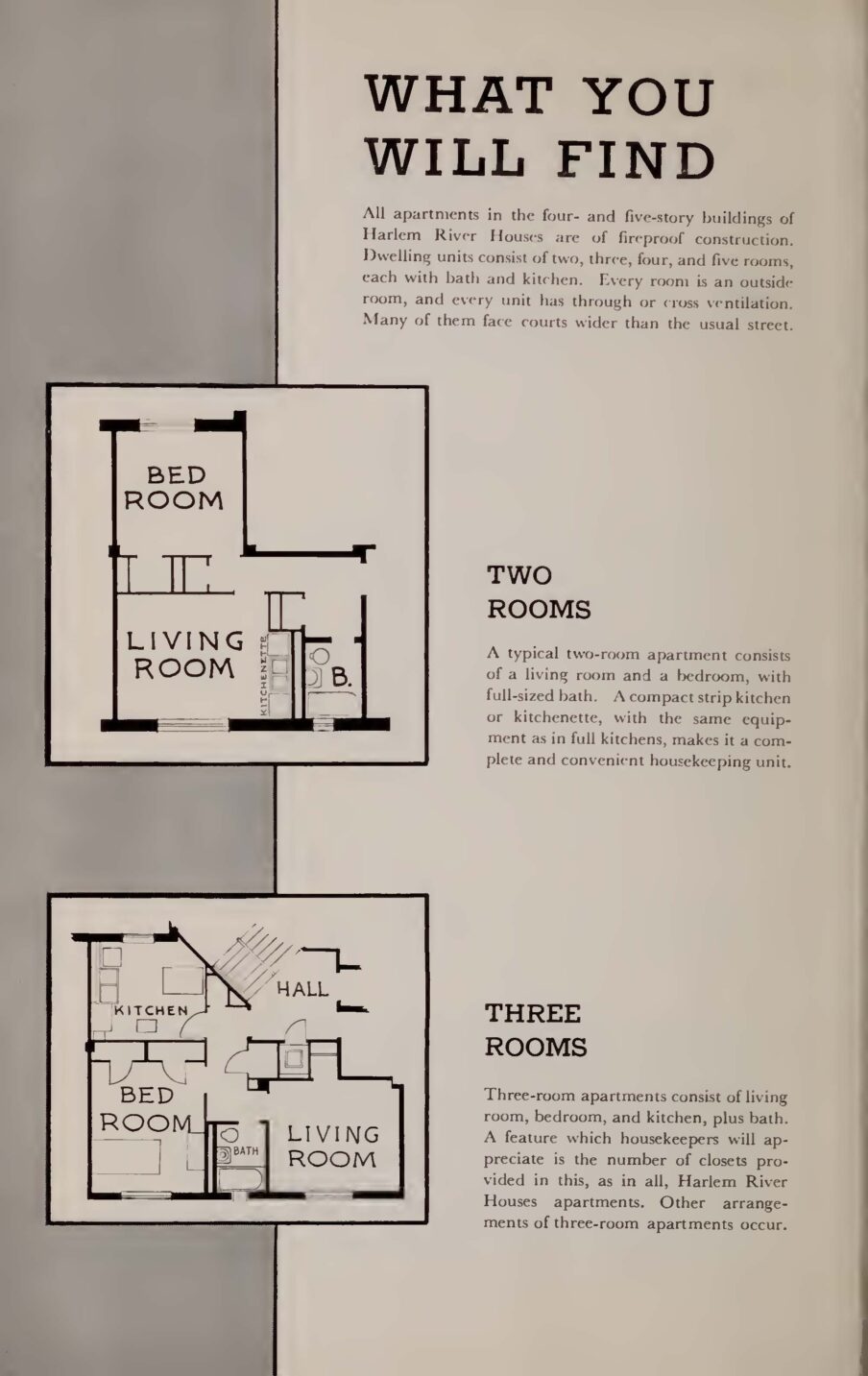

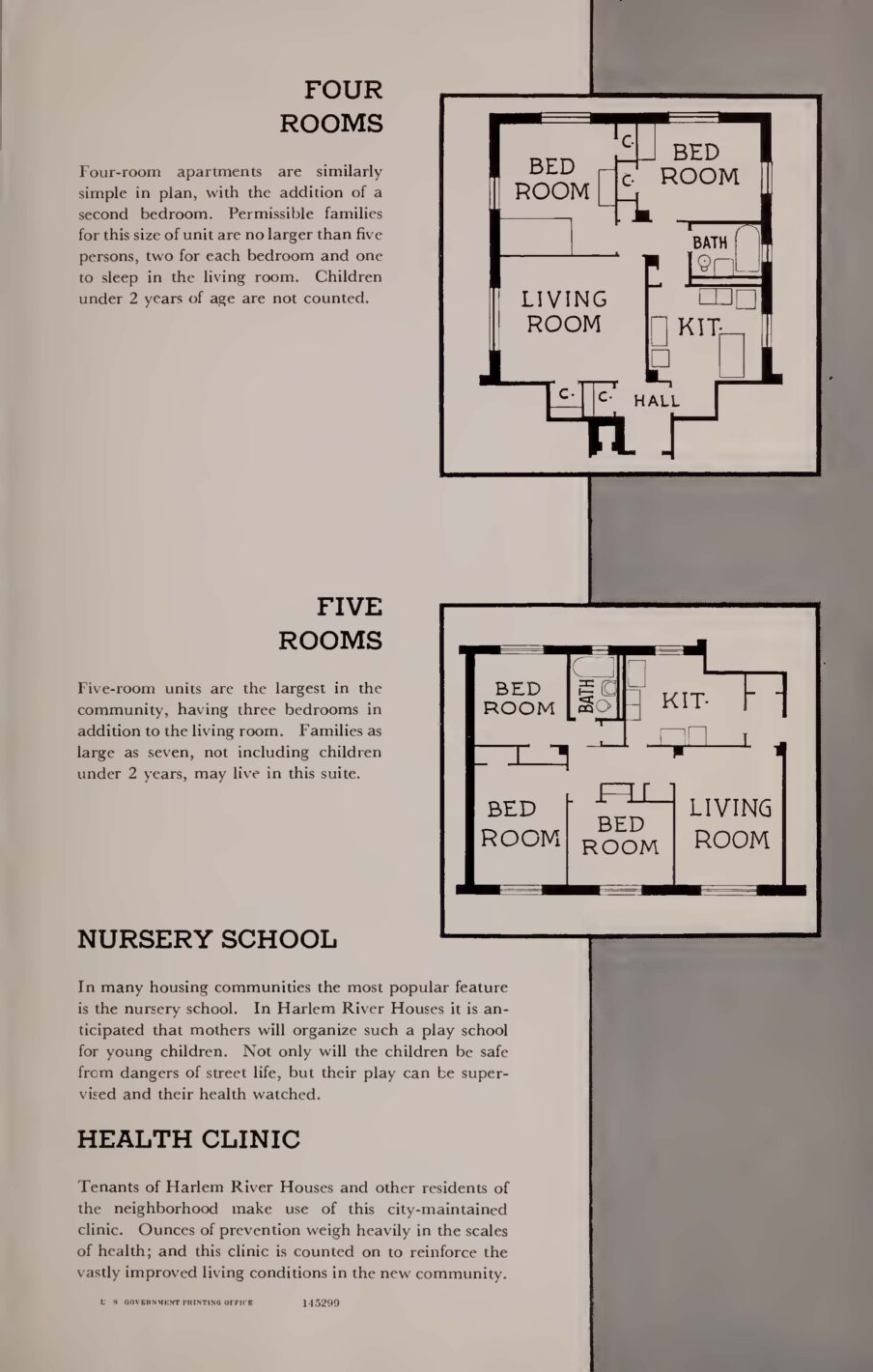

Pages from a government brochure describing the background conditions and built aspects of the new public housing development

Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works / Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works / Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

The Harlem River Houses is still seen today as a successful instance of public housing that has stood the test of time, an anchor of a long-standing Black community with many residents having lived there for decades, or even since its opening, according to a 1987 New York Times article, “At 50, Harlem River Houses Is Still Special.” Today, the project is often taught and visited as part of GSAPP’s architecture program, due to its innovations in modern housing and role in the city’s urban development history. Hilary Sample, the architect and professor who heads up the school’s core architect studio, says it serves “as a reminder of the urgent need for housing in New York City for the remarkable and historically Black community.”

Sources

Header Image: The American Institute of Architects, reproduced with permission

City of New York Manhattan Community Board 10, “Resolution: NYCHA Harlem River Houses Historic Rehabilitation”

Federal Administration of Public Works, “Harlem River Houses“

National Trust for Historic Preservation, “The Experimental History Behind the Harlem River Houses”

The New York Times: “At 50, Harlem River Houses Is Still Special,” “John L. Wilson Jr., 91, Architect Of Harlem River Houses, Is Dead“