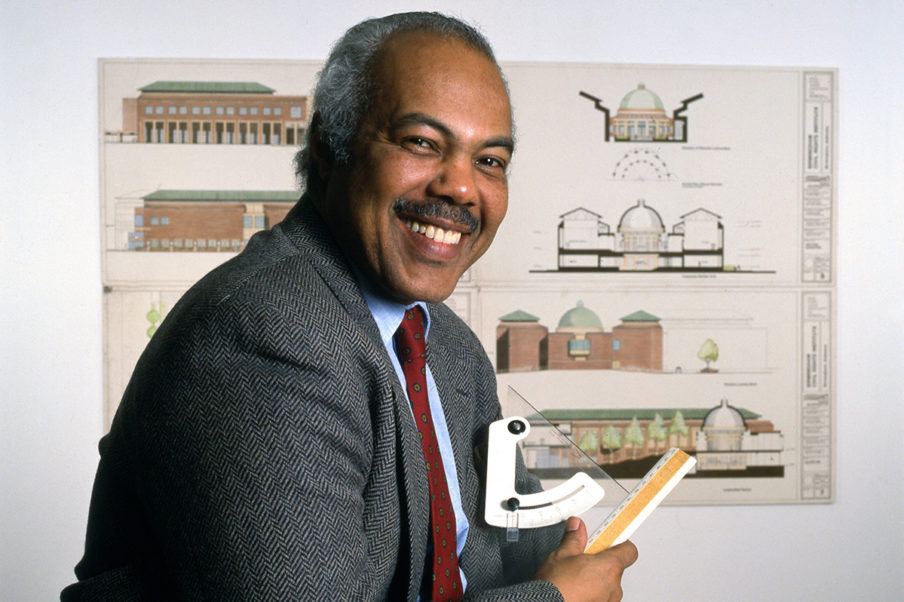

J. Max Bond Jr.

J. Max Bond Jr. exercised both an internal and outward focus on social inclusivity in architecture, which is illustrated in his involvement with ARCH, the Architects’ Renewal Committee in Harlem. After the organization was founded in 1964 by C. Richard Hatch, Bond served as the second executive director from 1967 to 1968. ARCH’s pursuits were manifold, and included a redevelopment plan with the Community Association of the East Harlem Triangle, distribution of material detailing tenant rights, the diversification of the New York City Planning Commission as well as the development of the Architecture in the Neighborhoods program which, in partnership with The Cooper Union, provided pre-architectural training to students in New York. ARCH did not only contribute on the local level, but helped to instantiate community participation into the planning and design process of cities across America, a design component currently considered integral to many practices.

While Bond’s dedication to creating a more inclusive architectural discourse shined through his teaching, his expression of the black experience, solely through form, is both nuanced and robust. The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change clearly represents Bond’s modernist proclivity, historical design agenda, and inflection toward local culture. For this project, Bond maintained that in addition to the program or the client, who constructs a building should influence the material choice, the contracting procedure, and the design goals. For the Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Bond chose brick for the façade as a means to employ the many professional bricklayers living in Atlanta at the time. The repeated arches Bond incorporated into the design pay homage to Black design; Bond explained that when you don’t have much, you build with what you have, and that has characterized the additive process that underlies Black architecture in the United States. By embracing larger social contexts in the formal investigation of his projects, Bond was able to design impactful buildings that exceed their visual splendor.

The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

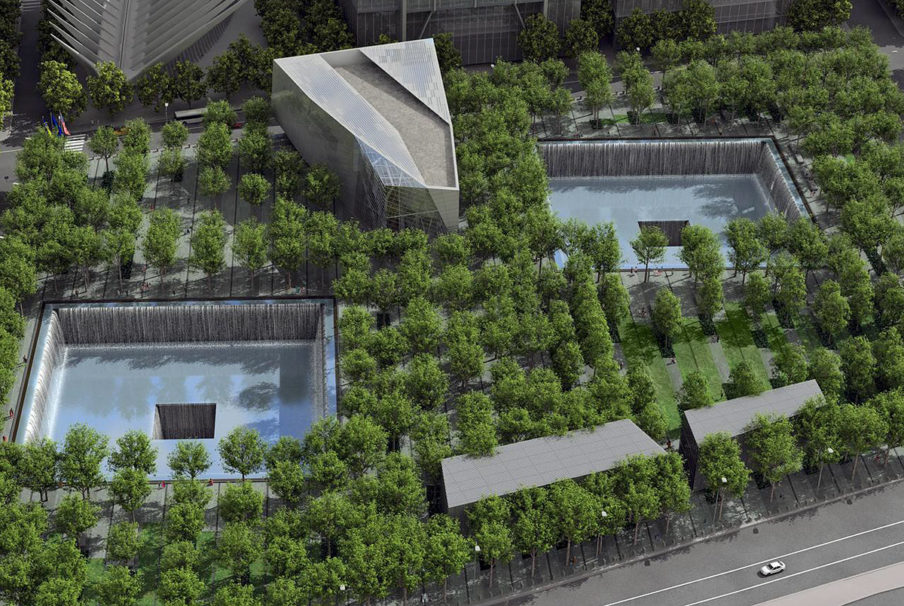

National September 11 Memorial Museum

Education

James Max Bond Jr. graduated from Booker T. Washington High School at age 13. He received his A.B. from Harvard College in 1955 and earned his Master of Architecture from the Graduate School of Design in 1958. In 1969, Max co-founded the architectural firm Bond Ryder Associates with Donald P. Ryder, becoming one of most prominent Black architecture firms in the country. Bond started teaching at Columbia University in the Graduate School of Architecture & Planning in 1968 and sat as Chairman of the Division of Architecture from 1980 to 1984. After Columbia, Bond served as Dean of the School of Architecture and Environmental Studies at City College of New York until 1992. In 1990, Bond Ryder Associates merged with Davis, Brody Associates and in 1994 and the firm became known as Davis Brody Bond (and eventually Davis Brody Bond Aedas). Davis Brody Bond was selected to design the National September 11 Memorial and Museum at the World Trade Center, but Bond passed before the design process was completed. In 2008, the New York chapter of AIA awarded Bond their medal of honor, where he is noted for saying It’s important for us, yes, to appreciate innovation, and recognize genius, but we should also question the deification of what I call Neoformalism. We should advocate for an outreaching, inclusive architecture, that responds forthrightly to the social, ecological, and cultural issues of this time, and for our grandchildren’s future.

Sources

Header Image: American Architect J. Max Bond. Anthony Barboza/Getty Images, ThoughtCo.com

Civil Rights Institute, CivilRightsTrail.com