Design & the Built Environment

Our lives and selves are shaped by the habitats we construct around us. The scale of humanity's ability to build or construct environments is a defining feature of our existence on our planet.

From antiquity to the present humanity has passed down the design principles of our built environments through cultural norms and academic institutions. This tradition of building or designing has evolved greatly due to technological advancement. Our constructed environments: our homes, schools, neighborhoods, transportation options, and infrastructure carry us through our lives.

Without what has been constructed all that our societies are today would cease to be and our experiences on this planet would drastically change. Our lives are contained within these spaces designed, by other individuals, and most of these authors are nameless and faceless to us. As we live our lives we tend to take for granted the forethought, planning, and intentions that went into the very streets we pass through.

The City Streets of Tunis, in the Medina: Cities all around the world look differently each with character as unique as their culture. In the Medina of Tunis, ancient architectural & urban planning practices created a very dense and walkable city center. The design and craftsmanship of the Medina is evinced by its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

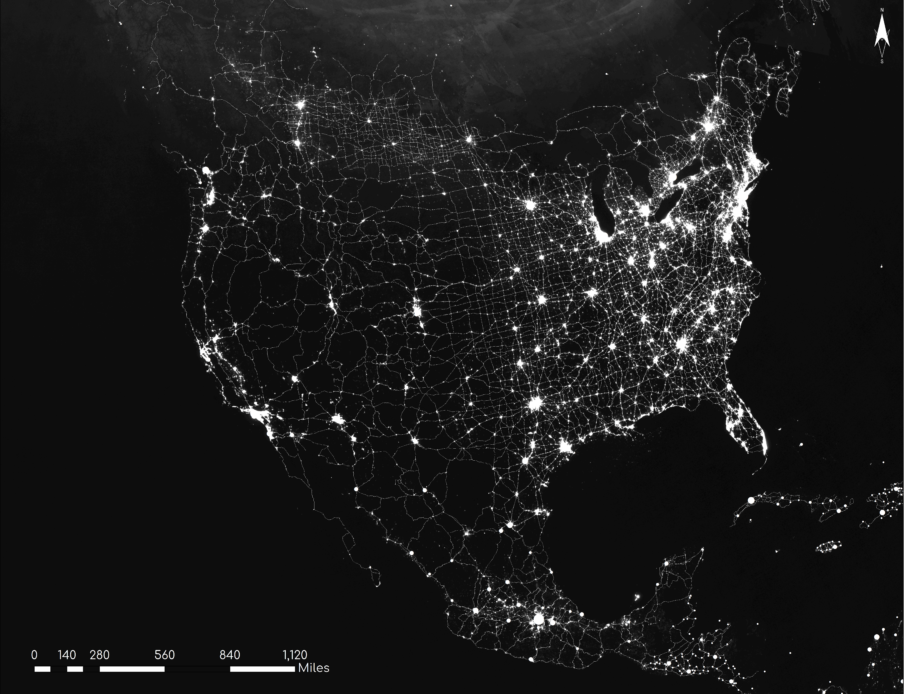

Highways & City Lights from Above: Phenomenon such as light pollution, the urban heat island effect, and ecological degradation are all resultant of urbanization. Many cities are retroactively investigating ways of mitigating these effects as we come to understand the harm we enact on the natural environment.

The buildings’ architects author hold our memories, they facilitate our interactions with each other and provide us with shelter, comfort, and security. The cities we construct allow us to live close to each other in community, with clean water, electricity, and sanitation. They allow us to work and play among the range of leisure and recreational activities that exist from museums to parks, to libraries, theaters, etc.

How each city is connected through transportation systems allows us to travel throughout our metropolitan regions by rail, plane, or car. The ease of travel between cities encourages us to remain connected to our larger social networks and experience the larger world around us through exploration. At the scale between the building and the region are the landscapes that punctuate our environments with wildlife, plants, and abundant ecologies.

From the building to the city, to the landscape, these are our built environments and they have an extreme effect on not just our personhood, but our societies and the planet. There’s a reason our built environments are highly charged spaces organized by political leadership and governance. While seemingly innocuous, the small mundane choices add up. If we’re deciding where a new building goes, whether or not we choose to build light-rail or a highway, or even whether we preserve naturalized areas or auction them off for real estate development, eventually all of these small decisions accumulate and begin to have lasting implications for our cities and ultimately the world as we urbanize more and more land.

View of Manhattan from Roosevelt Island: The cities we have today are the result of countless decisions made by residents, designers, property owners, real estate developers, and political leadership. In this image each building has an owner, an architect, and houses the daily operations for thousands of people, companies, and institutions.

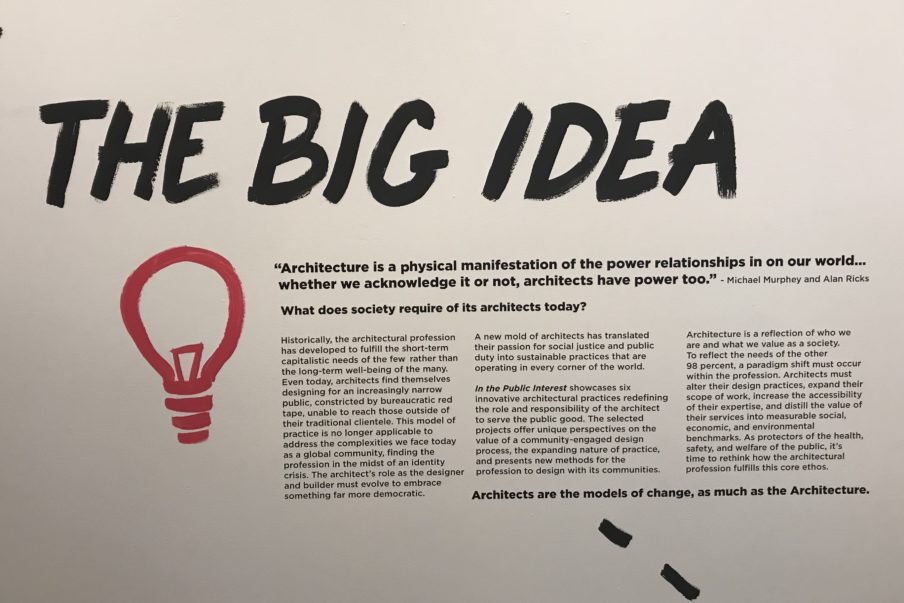

Image from the exhibition "In the Public Interest: Redefining the Architect's Role and Responsibility". An exhibition created by Garrett Nelli Assoc. AIA at the Center for Architecture and Design in Seattle, Washington.

What we construct becomes relatively permanent and those decisions can’t be undone without significant public disapproval or a massive change in urban development trajectories. Massive transportation investment in highway expansion cannot be easily reversed. You can’t delete a highway after deciding a light or high-speed rail would’ve been more socially and environmentally equitable. Similarly, you can’t undo deforestation once all naturalized space has been converted into built space.

So what happens when our histories tell us that the ways we’ve constructed our world haven’t always been aligned with notions of equality, justice, and beneficence? What happens when the flaws of our past become the defining norms and contentions of today?

While what we build, what we construct, has a degree of permanence, time is a powerful agent of reformation.

History shows that as our societies progress some of the darkest aspects of our choices are enacted spatially, that is to say in what and how we build. The power of aesthetics and of design are multifaceted and seemingly illusory. We can build spaces to elicit joy and community as well as spaces that encourage crime and intimidation. There is an intention in the spaces we design that corresponds to the intended use and purpose of those spaces.

We don’t design houses and stores the same, yet we can perfect the design of a home in terms of the comfort and the respite it provides just as much as we can perfect the design of a store to create the most appealing experience for the customer. Design is more powerful when coupled with an intention, and often, that design intention is pursuant to the desired outcomes or goals of that design. When designing a home, the goal is to design a home someone will want to not only live in but purchase or rent. When designing a store again the goal is to design a space that entices someone to become a customer.

Design can be very persuasive and almost commanding in what it wants the user to do, because design engages with us at an emotional and psychological level. This is because design is deeply human. Historically, we understand that humanity has gone through various dark moments of extreme wrongdoing sociologically and politically. As our histories show us the moments of prolonged social inequity and violence are deeply embedded in the design choices of our built environment.

The inequities that exist in what we design mirror our social, political, and economic inequities.

Africatown Community Meeting: Community organizing has been a method of resistance and empowerment for centuries. For black and brown communities around the country neighborhood based movements are filling a void of municipal and federal leadership as it pertains to ensuring the liberties of black and brown communities.

Community Action: Taking ownership of one's land through public art and community engagement can reinvigorate the soul of a community or a neighborhood.

De jure racial segregation in the United States was a profoundly social, political, and economic phenomenon. However, what is intensely underscored by the concept of segregation is its implications on the built environment. The fundamental position that one group of people could not exist or co-mingle in the same space with the other, is a charge to create two different worlds, two different environments. With the famed line that, “separate is not equal” that emerged in the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 there was a call to end this vision of a split world and usher in a unified country. Segregated development patterns created sprawled metropoles, deepened socioeconomic inequality, and divided America by color. The charge to end segregation was not a charge to undo decades of bad design choices and centuries of enslavement. It was simply a charge to not segregate in the future.

However, our built environments throughout the country were built to facilitate racial division prior to the supreme court ruling. Then that intentional decision to segregate was outlawed and abandoned formally by the government of the United States. However, segregated America at that point had already been built, the project in a sense was “finished” and the inequities were already concretized for generations to endure.

For any black American being raised in this era of American history, the notion of ownership of one’s life and property was difficult to imagine as their freedom to live where they desired, to go where they pleased, and to follow their dreams was not possible even without de jure segregation.

Imagine Africatown: Africatown is a black owned community land trust in the Central District of Seattle. Each summer they ask the City of Seattle to imagine a future for the historically redlined neighborhood.

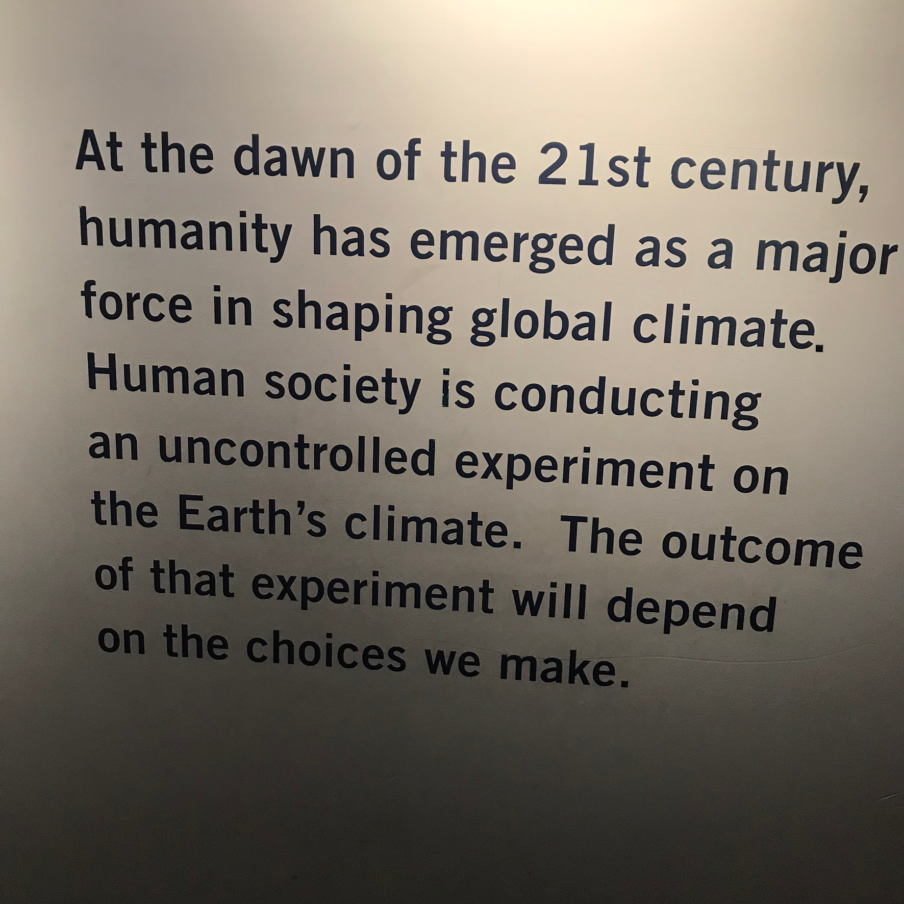

Now presently on the cusp of a new decade, the year 2020 brings many familiar challenges to our country and our built environment. The inequalities that exist today are residual of what we have not yet reconciled from the past. Furthermore, the warming of the planet, the threat of ecological collapse, and climatic disarray are symptomatic of just how wasteful, destructive, and irresponsible our development patterns have been for ourselves and the planet.

Yet in what we build and what we construct there is a degree of permanence time is a powerful agent of reformation.

The silver lining is that design is a process of change and evolution that predates modern society. How we chose to live then and how we choose to live now is connected by our ability to change and evolve. With time we change the ways we live because of social, cultural, and technological innovation.

Image taken from the Harvard Museum of Natural History's Exhibit on Climate Change titled "Climate Change: Our Global Experiment"

Harvard GSD Professors Stephen Gray & Alex Krieger and first year Urban Planning and Design students touring the Boston John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum (2017)

Humanity has lived a multitude of different ways and our culture and institutions change rapidly. Compare 1919 to 2019 and contemplate the degree of social, political, technological change that occurred during those one hundred years.

Now consider 2019 to 2119.

Our families young and old will inherit our built environment and pass it to those who come after them. The connection between the past, present, and the future are all mediated by our relationships between each other and our constructed environments.

Position yourself in that one-hundred years and imagine your role in shaping the change we need now more than ever.

It's important for everyone to see themselves as an agent of change in the world we create. The way our world has been built and designed impacts everyone, so what happens when we encourage everyone to take part in designing our future?

Change must be designed and implemented into the world. Recognize that we need designers participating in the imagining and creation of a world beyond the one we have today and while that leaves a lot to be discussed, debated, and analyzed, there is much more that needs to be built to ensure the future is more just and more equitable than what we have presently.

Our future needs to be materialized through the construction of change—to signal a pattern break in how we choose to design our neighborhoods, cities, and landscapes to create a more democratic, innovative, creative, and environmentally restorative future.

We need to encourage and inspire members of all generations to participate as we design this new world, and we must seek out and empower those who have historically been underrepresented in this process. This is a time where we need to encourage more people to become designers across the board but keep in mind those who’ve been marginalized historically: Black Americans, Indigenous communities, Latinos, LGBTQ+, immigrants, women, and working-class Americans. The inequities in the authorship of our built environments are vast but the doors are opening to repair those legacies. We need to encourage at all levels of education adopting design curricula and exposing everyone to these professional and vocational pathways early. The earlier we learn about pitfalls of architecture, urban planning, and landscape architecture as well as the potentials they hold for the future the quicker we will have a generation of designers prepared to take on the challenges of today head-on.

A Design Cypher: Seattle & Central District Community members came together to imagine the future of five sites in their neighbood. After a site visit there were three rounds of design: a collage, a site plan, and a 3D model. GSD Alum's in photo Sara Zewde & Azzurra Cox.

Sharing the Results: After the final design round passed each of the five groups took turns explaining their design proposal to the group. President of Africatown Seattle K. Wyking Garrett seen taking a photo of the model.

Design requires learning how to communicate ideas through representational techniques such as drafting, sketching, and illustration. Design requires the capacity to analyze diverse situations and conduct research investigations to illuminate solutions, but more importantly, design underscores the degree to which the world can change. For black Americans, this means encouraging our youth to see the world as a place they can actively shape and influence, by pushing them to see themselves as a designer of our world. There is a deeply creative and imaginative quality to the notion of design, the idea that we can imagine complex solutions or innovations to problems and bring them to life. Design from that perspective is profoundly empowering.

The Design Nexus is a project that seeks to catalyze those efforts, of sparking the realization in the minds of our future generations that the world is theirs to transform should they learn the tools to create that change. Although, that change might be technical at times and often you need the patience to actualize it, it is only because the solutions to our world are the most complex that they’ve ever been.

Our built environment is our greatest asset but is also our most contested creation. Our future on this planet and the condition of that future depends on how we resolve our contestations, imagine a better world, and commit ourselves to its creation. The built environment of the future will need to support us because it is the mechanism through which we live, survive and thrive. The built environment is our vehicle to a brighter future and its fate is in our hands.

All images and text by Gabriel Ramos