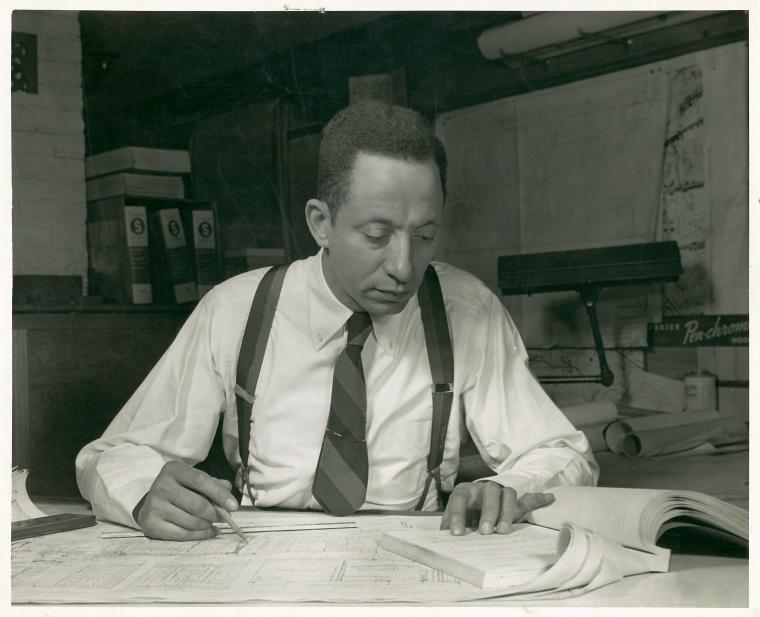

Hilyard Robinson: A Visionary Architect of Social Change

By R. Kofi Bempong

Hilyard Robinson, a pioneering African American architect, reshaped public housing in the United States with his innovative, community-focused designs. His notable projects, including the Langston Terrace Dwellings and Aberdeen Gardens, exemplify his commitment to social reform and architectural excellence. Robinson's enduring legacy continues to influence and inspire future generations in the field of architecture.

Hilyard Robinson was born in Washington, D.C., in 1899; Robinson emerged as a pioneering Black architect when racial segregation and economic disparities starkly divided America. His career, closely intertwined with the societal transformations of the mid-20th century, showcases his dedication to community-oriented architecture. This narrative explores Robinson’s life, his architectural philosophy, and his lasting impact on urban housing, with a spotlight on his most acclaimed project, the Langston Terrace Dwellings.

Early Life and Education

Robinson’s early exposure to Washington, D.C.’s architectural diversity and underlying social inequities fueled a lifelong passion. After serving in World War I, Robinson pursued a formal education in architecture at Columbia University, where the Beaux-Arts architectural style significantly influenced him. Renowned for its grandeur, symmetry, and elaborate ornamentation, Beaux-Arts architecture draws heavily on classical Greek and Roman influences, featuring columns, arches, and luxurious materials like marble. This style is particularly evident in public and institutional buildings, symbolizing cultural prestige and power. His education didn’t stop at Columbia; he further honed his craft at the University of Pennsylvania and later at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This European venture offered him a global perspective on architecture as a tool for social reform.

Architectural Philosophy and Career

Returning to the United States during the Great Depression, Robinson found a country in dire need of reform and modernization. His design ethos evolved into a blend of aesthetic elegance and functional pragmatism, underpinned by a profound commitment to social welfare. Robinson’s philosophy was clear: architecture should serve the community, foster well-being, and promote equality.

One primary area in which Robinson applied his principles was public housing. He became a key figure in public housing design, advocating for and implementing economically feasible and culturally sensitive designs for the communities they served. His approach often contrasted sharply with prevailing public housing models, which tended to be austere and institutional.

Hilyard Robinson’s Architectural Legacy: Pioneering Community-Oriented Design

Hilyard Robinson’s architectural contributions are deeply embedded in the social fabric of the United States, particularly evident in his influential projects like the Langston Terrace Dwellings in Washington, D.C., and Aberdeen Gardens in Virginia. Both projects are significant milestones in the history of public housing and the evolution of community-oriented architecture.

Langston Terrace Dwellings, one of the first federally funded public housing projects in the United States and the first designed by an African American architect, was constructed between 1935 and 1938 under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration. Named after John Mercer Langston, a 19th-century American abolitionist, attorney, and founder of Howard University Law School, the project is a vibrant embodiment of Robinson’s commitment to integrating cultural identity into architectural design. The development features mural art celebrating African American history and communal spaces to foster social interaction. It was built with materials and labor sourced from the local Black community. In 1987, its cultural and historical significance was formally recognized when listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the design of Langston Terrace, Robinson skillfully blended the International Style with elements of African art, creating an innovative aesthetic that garnered widespread acclaim. More than just a housing complex, it was envisioned as a living space that nurtured community and cultural pride among its residents.

Similarly, Robinson’s design for Aberdeen Gardens in Virginia during the late 1930s emphasized his philosophy of architecture as a vehicle for social improvement. Funded by the federal government as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, Aberdeen Gardens was designed specifically for African American shipyard workers and their families at a time when segregation severely limited housing opportunities for Black Americans. This project featured homes with spacious plots for gardening and recreation, illustrating Robinson’s vision of integrating natural environments with community welfare. Each home was crafted to support self-sufficiency, with space for growing food and raising livestock, reflecting a forward-thinking approach to economic independence and stability.

Robinson’s work at Aberdeen Gardens, like that at Langston Terrace, showcases his architectural expertise and deep understanding of his time’s socio-economic challenges. His projects continue to serve as pivotal examples of how architecture can be used to address social issues, foster community, and enhance the quality of life for marginalized populations. Together, these endeavors highlight Robinson’s enduring legacy in socially responsive architecture.

Conclusion

Hilyard Robinson’s visionary approach transcended buildings; it incorporated dignity, equality, and community into American architecture. His dedication to melding aesthetic beauty with functional living spaces for marginalized communities challenged and reshaped the conventions of public housing. Through his work, Robinson helped build communities that uplifted, empowered, and transformed lives, setting a profound precedent for future generations. Reflecting on Robinson’s contributions reveals that his legacy extends beyond his building designs to influencing urban development and social responsibility.

In today’s world, where social inequality continues to be a pervasive challenge, Robinson’s principles are more relevant than ever. They urge contemporary architects and urban planners to consider how spaces can foster community, support sustainability, and promote inclusivity. Hilyard Robinson’s life and work continue to inspire a holistic approach to urban development, one that views design not just as a technical skill but as a social art capable of healing and hope. Thus, his enduring influence reminds us that our shared spaces are places to live and thrive, echoing his belief that architecture can indeed be an instrument of social change.