The Legacy of Donald L. Stull: Ruggles Station

By Darien Carr

Donald Stull going over designs in their Boston office in 2010. WENDY MAEDA/GLOBE STAFF/THE BOSTON GLOBE

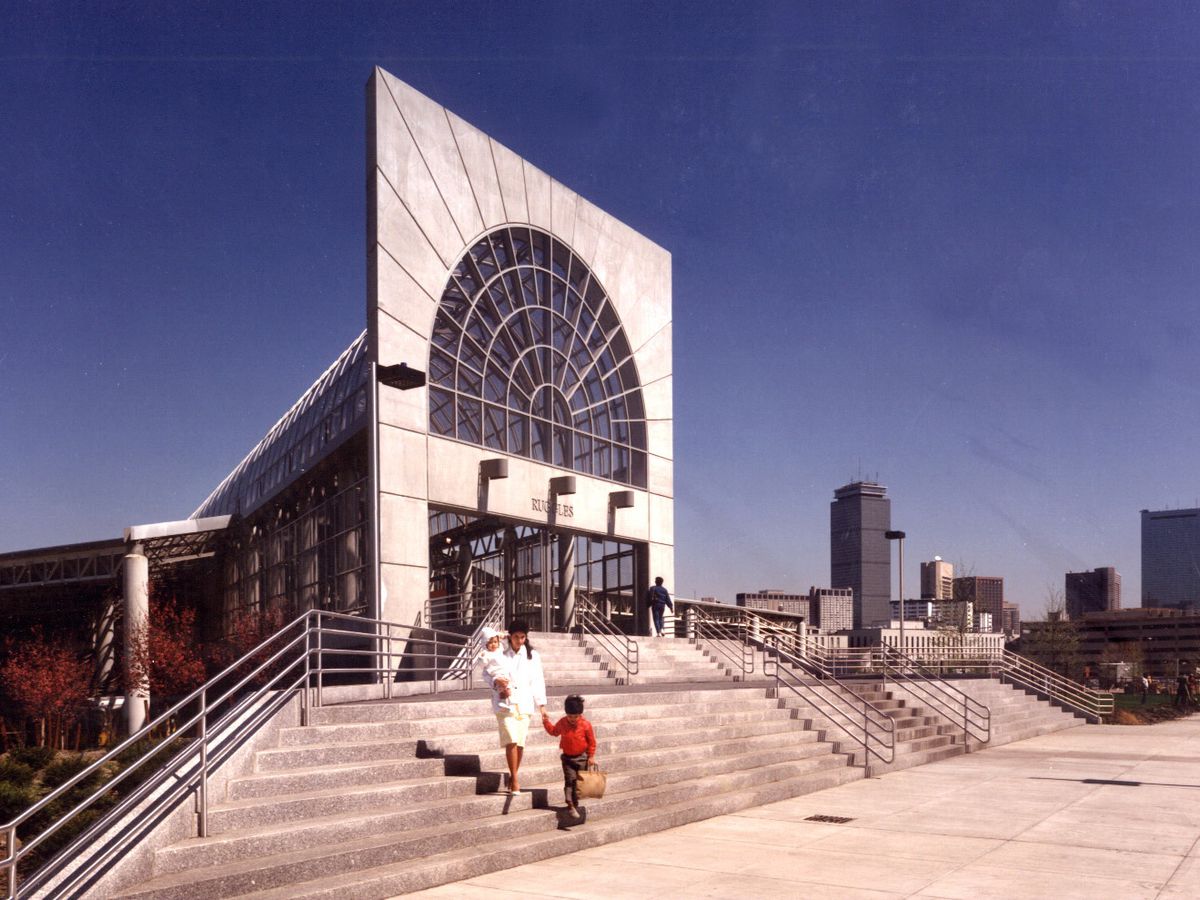

Ruggles Station is a building in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood with two faces, two fronts. One borders Northeastern University’s College of Engineering, and the other looks towards Columbus Avenue. The facade next to Northeastern is a wall running along the campus boundary. It isn’t connected to the station’s volume; nested behind it isn’t the building itself but an elevated road where MBTA buses arrive to pick up passengers. When you enter Ruggles on the Northeastern side, you move below the road, up an escalator, and find yourself at the beginning of this large urban walkway underneath a ribbed vaulted ceiling. Inside this walkway, turning right or left means catching a train, grabbing coffee, or waiting for a bus. Continuing straight, however, entails a rhythmic movement below a series of structural arches oblique to the direction you travel. Eventually, you’ll reach the building’s second face, the one looking towards Columbus Avenue. In the horizontal dimension, this facade is much shorter than the one along Northeastern’s campus. That said, if you were to approach the station from Columbus Avenue, it’s easy to misperceive as taller than it is. The facade is located at the top of a staircase that bridges an elevation difference between the station and the avenue below it.

To encounter this building is to encounter the architecture of Don L. Stull and M. David Lee, two pioneering Black architects whose work includes eight other train stations, Boston’s Roxbury Community College, and the Harriet Tubman House. Their firm, Stull and Lee Incorporated, was initially founded by Stull in 1966 under the name Stull Associates. During a time when there were very few practicing Black architects, Stull built a practice that would inspire future generations of Black designers.

David Lee began working with Stull in 1969 when he was still a student at the GSD. Seventeen years later, Stull and Lee decided to collectively change the firm’s name from Stull Associates to Stull and Lee Incorporated, one year before Ruggles station first opened its doors to the public. “I’ve been told by many young Black architects who started firms that our firm had been a model for them”, Lee explains to the Boston Globe. “A lot of them looked first to Stull Associates, and then to Stull and Lee. Everybody wanted to work at Stull and Lee.”

If one of Stull’s legacies lies in the way he inspired and mentored future generations of Black architects, another lies in his built work. His approach to architecture was philosophical in the sense that his buildings (re)structure the relationship between social interactions, movement, and program. For example, when designing Roxbury Community College, Stull began the project by reworking definitions of education and learning. It led to a design that prioritizes the informal interactions of a college student’s educational experience. “[I]n a learning environment, the critical question is not how quickly you can get there but what happens to your mind on the way”, Stull remarks in a 2004 interview on the project. “That’s one of the reasons Roxbury Community College is not one big mega-structure building, but a campus.” It becomes a space that defines learning as consistently en route. It showcases the sensibility towards an architecture that constantly arrives.

Stull’s attention to the things that happen on the way, then, becomes apparent walking through Ruggles. Being inside the station means inhabiting the space between the building’s two faces, two fronts. Front here is taking meaning from Frontin’, a state of pretending. Ruggles station’s facades are fronts that act like a mask. They present a surface to the city around them, and by doing so, they disguise what’s happening on the inside of the building; there, an urban pathway with a vaulted ceiling appears to be a one-to-one sampling of a classical ribbed motif that can be traced back to Romanesque architecture. However, walking through the space, it becomes apparent that these arches are not classical. The ribs are diagonal to the walkway itself, signifying an important distortion within an otherwise uniform scheme. The formal move evokes a new interpretation of an existing body of architectural knowledge. Situated between the building’s two fronts, it is a move that makes the building feel like it is code-switching, oscillating between vocabularies. Walking through Ruggles calls attention to the dissonant sounds produced by this oscillation and the beauty within those frequencies.

These details exemplify a main tenet of Stull and Lee’s work— subverting the status quo. It makes sense, especially after hearing Lee talk about the work he did with Stull:

I often use a parallel around music, and I talk about the song My Favorite Things. There is a version by Julie Andrews, and there’s also a version by John Coltrane. Same song, but very different DNA, and I like them both. So what we were trying to do was to figure out how to take what had ordinarily been kind of a white Angelo Saxon male [sic] dominated aesthetic, and figure out how one could introduce another interpretation of those forms.

It is through this process of re-interpretation that Stull and Lee’s work reimagines what’s already there. Their work remixes the spatial vocabularies typical to architecture, and situates them within communities architecture has tended to ignore. It’s a purpose that exemplifies the main tenet of Stull and Lee’s approach— engendering equality through disjointed harmonies.

Donald L. Stull was a groundbreaking architect who passed away on November 20th, 2020 in his home in Milton, MA. as 83 years old. He was born in Springfield, Ohio, and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Ohio State University in 1961. Subsequently, he received a Master Degree from Harvard in 1962. Through his practice and example as an architect, Stull created award-winning, transformative design projects and served as an inspiration to many. The AADN would like to take this space to remember his legacy.