The Nexus Excerpts: Rob Problak Gibbs

Rob Problak Gibbs speaks about the importance of hip-hop, graffiti, and blackness to his creative practice.

Stylized photo illustration of Gibbs holding his paintbrush, an aerosol can. DIANA LEVINE / GLOBE STAFF PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

TARA OLUWAFEMI [T.O]: What is the vision of blackness that you are trying to portray through your work? Is this a focus on the world as you see it or how you would like it to be?

ROB PROBLAK GIBBS [RPG]: I do work that highlights the way we exist. To think about the underrepresentation or the future of… I think you have to talk about what’s current. My work is geared towards an audience in communities that I’ve done it in. People that can look at these murals and call them mirrors at some point, to see themselves represented.

We have a balancing act to do in the city and in the culture, period. To be an advocate in hip hop, I have a responsibility and with a skill set that gets a lot of good attention I want to be able to break that down. To the point that I’ve recently started thinking, “wow, I’ve fallen into the seat of being a storyteller.” The stories I’m telling are like open-ended conversations so that people can collaborate and add on to it. They may not be able to know the narrative or the details of the particular pieces of work that I do, but it’s open-ended enough for them to always talk about how they felt when they seen it.

My work is just a way to be able to add on to those conversations because it’s building a morale— a boost of pride— from being represented on such a large scale. It’s not just like, “oh, that’s cute, it’s at an after-school, or it’s temporary.” It’s like, “nah, these are pieces that have permanence in the communities and almost become like landmarks.” It’s super cool— you can Google Map an address and the work pops up. So that just means that, “OK, we know what’s happening around here, or have an idea or a clue.” So I feel like my view of blackness, in its current existence, is just showing who’s here, who’s moving and shaking, through the kind of nuances that I play into the pieces.

T.O: For a lot of your murals, you’re painting people. Are they based on real people that you know or are they an amalgamation of different traits and features from different people?

RPG: The imagery that I’ve been recently depending on comes out of the innocence of a child, and being able to put that into the future in a way where young people are going to be able to resonate with seeing something. They might see a little boy or a little girl they probably went to school with, or one they live around the way with, or one they see themselves in.

So I feel like, when that messaging is there, or that type of representation is visible— it’s not based off of anybody specifically, I don’t have models or things of that nature— I’m just pulling together references, where I kind of Frankenstein images. I’m like, “Okay, if I could exemplify happiness to the utmost, right? Without clearly telling you to ‘don’t worry, be happy’, or be cliché about it, how could I do that?” It’s the expression of feeling where, I think, words only limit what you come up with.

It’s not a lab where I’m sitting here and I’m trying to cook up— like, “Okay, this is who I have to connect with, with some type of intention.”

If I get your attention with what I’m able to do, when it comes down to the messaging— or we want to tell a story where we add historical figures or people that are within the culture that you’re going to be able to recognize— I want you to be familiar with the style. So the visual language is something that— you know, with me and the crew that I paint with— we’ve been very intentional about how and what we put out, you know, the palettes and things of that nature that just celebrate and emphasize Black culture.

DARIEN CARR [D.C]: Related to that point on culture, how did music affect how you are building this worldview, how you are building these things and integrating them into your work? You mentioned style and expression and I know graffiti is a main part of a lot of the work you do. Could you speak to music in relation to how it relates to your understanding of your identity as a person who’s Black, and a person who’s a creative?

RPG: Aw man, music, you know, Black culture and Black people that are the archetypes to a lot of music that we rock with, you know what I mean? Hip hop being something that is the metronome to my work. I see a lot of relevance in it. For songs that don’t have visuals to them, the imagination or the encouragement that you get from it can be like the visuals—the music video or the album cover—to these particular tracks, or series of tracks.

Just imagine if all the music I listen to, I made into a playlist. And then that playlist had a playlist cover. Whatever pieces that I create definitely reflect from, you know, the music that drives me to kind of tell some of that narrative. I think some of the stories that we can relate to are embedded in the beat. And I feel like when it’s delivered in that particular manner, this is just a support to that.

Music has a high-high-high influence on what I do, man, I can’t live without it. I was bumpin’ beats before we got into this interview just to get my mind right. Because depending on the artist I’m in the mood to listen to, man, it really gets my mind like, you know, thinking in that path, whether it’s instrumental or vocal.

D.C: This reminds me of sampling and the act of taking stories and recontextualizing them through a medium, whether that be sound or paint. Could you speak to your work in relation to sampling and how the act of bringing together stories comes out in your visual medium?

Such an interesting comparison to sampling. With sampling, and the things that were created to invent new pieces, you have to give these stories the time that they deserve. Whether you’re living with it or your experiencing it, it’s a way to hit the rest of the world with what I call like the Sankofa Spirit, you know? To be able to look back at your past, to be able to contribute to a brighter future, would be the ultimate way, you know? You could take a saying from something you heard your grandfather say, or something your pops would always tell you, and then put it in a line. Or you could pull a line from a song, and title it as a piece— it’s all inspiration.

And how to pull all that stuff together: man…

I would say if you look at some of the nuances in the work that I do— whether it’s the clothing that the characters are wearing, or something that’s in the representation of the album artwork that was out there— anything that can tie the mood to the influence, so that people could connect to it and could build upon that.

These are just old stories told in different ways. If you take the responsibility of a Griot, your responsibility is to pass on those stories so that others could contribute to it. And in my murals and artwork, I’m trying to activate that space in conversation so that people can talk to what I’m steering them towards, or at least feel good in a place.

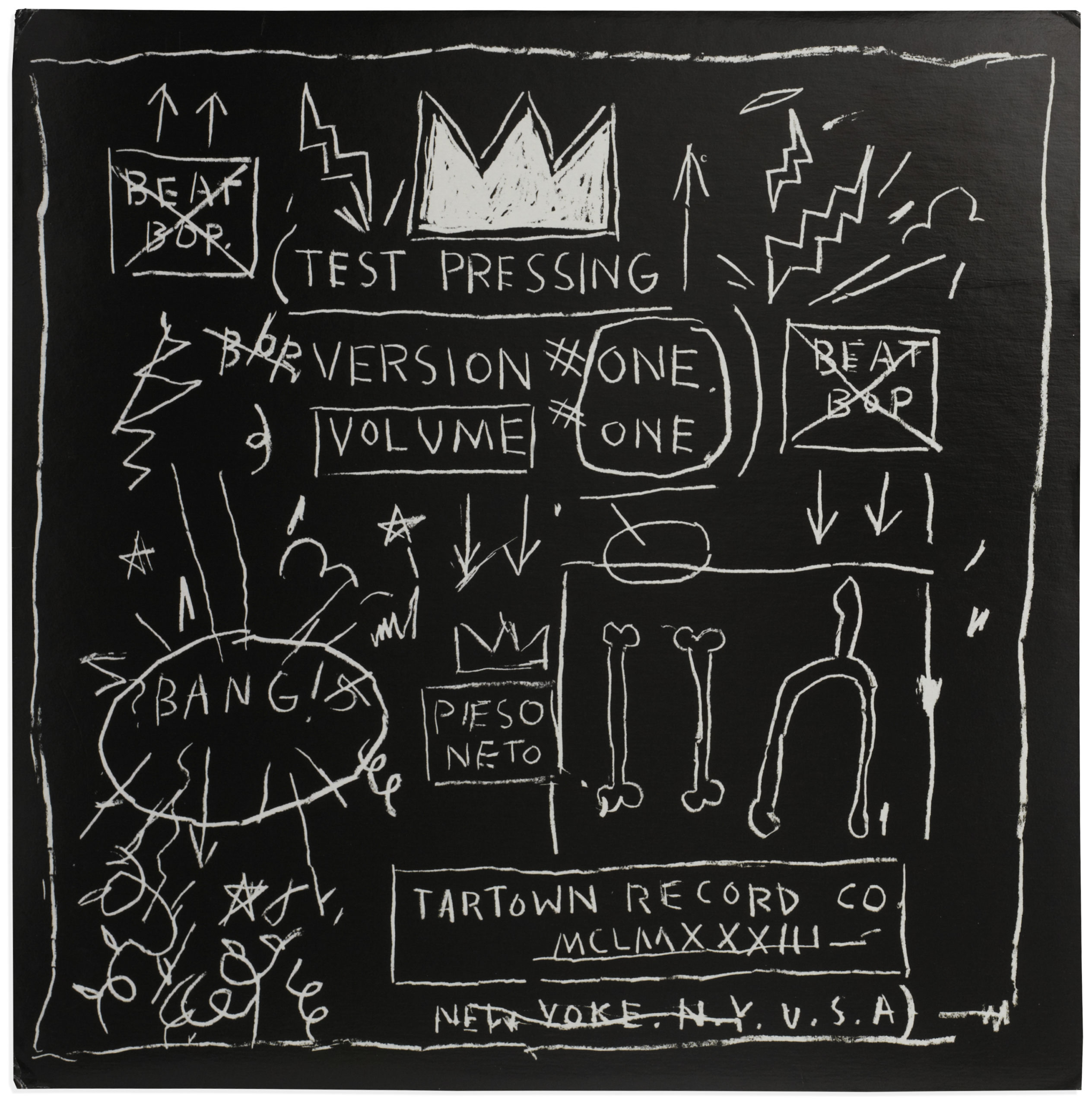

T.O: That’s a great comparison between music and visual art. Basquiat was known for doing graffiti, but he had also created album covers. What first drew you to graffiti as a medium? I’m very interested in the idea of your work becoming this large plastered album cover.

Looking at all the disciplines in the culture, there was something that I had to pick that I could be good at, you know?

I felt like when I seen my first piece of graffiti, or I seen it activated in a space, I was like, “wow, this is a play on the alphabet.” And Alphabet, regardless of what language you translate it to, is universal. In the hip hop culture I was like, “damn, graffiti is hip hop’s alphabet”, you know?

Now just imagine the alphabet with accessories, and how you could take the words from a deejay that gets cut up and you can put it in an outline of a piece. You can add an accessory to that piece where, you know, you see the b-boys and the b-girls on the end which are characters that you add onto the piece, or you could take the lyrics that emcees rap and you can do a whole composition, or a whole mural, from it.

I was exposed to graffiti from around the world through a book called Aerosol Art. It made me want to see myself do graffiti on a higher level. For the men and women that were in the Aerosol Art book, I was modeling what I thought was the way, the blueprint, you know what I mean? I even compare it to hieroglyphics to an extent; with the Aerosol, we’re putting marks on the wall, we’re highlighting culture. And within graffiti there’s the individual that really gets really big on their name, but then there’s the other graffiti writers that celebrate the culture.

And I’ve been turned on by participating in celebrating the culture by doing these larger mural compositions— we call them Productions, you know what I mean? And in those Productions, it’s a combination of portraits, characters, letters, background… Very scenic. Like, you know, taking up the entire wall space from top to bottom, left to right.

Continuing on that album cover theory, like, if you had opened up the album cover, and it was like a two page spread, or a three page fold out, these Productions mirrored imaging that was continuing that story. Where you had a picture that was worth a thousand words, but it can’t just exist on one picture, it has to be in a series of pictures, you understand?

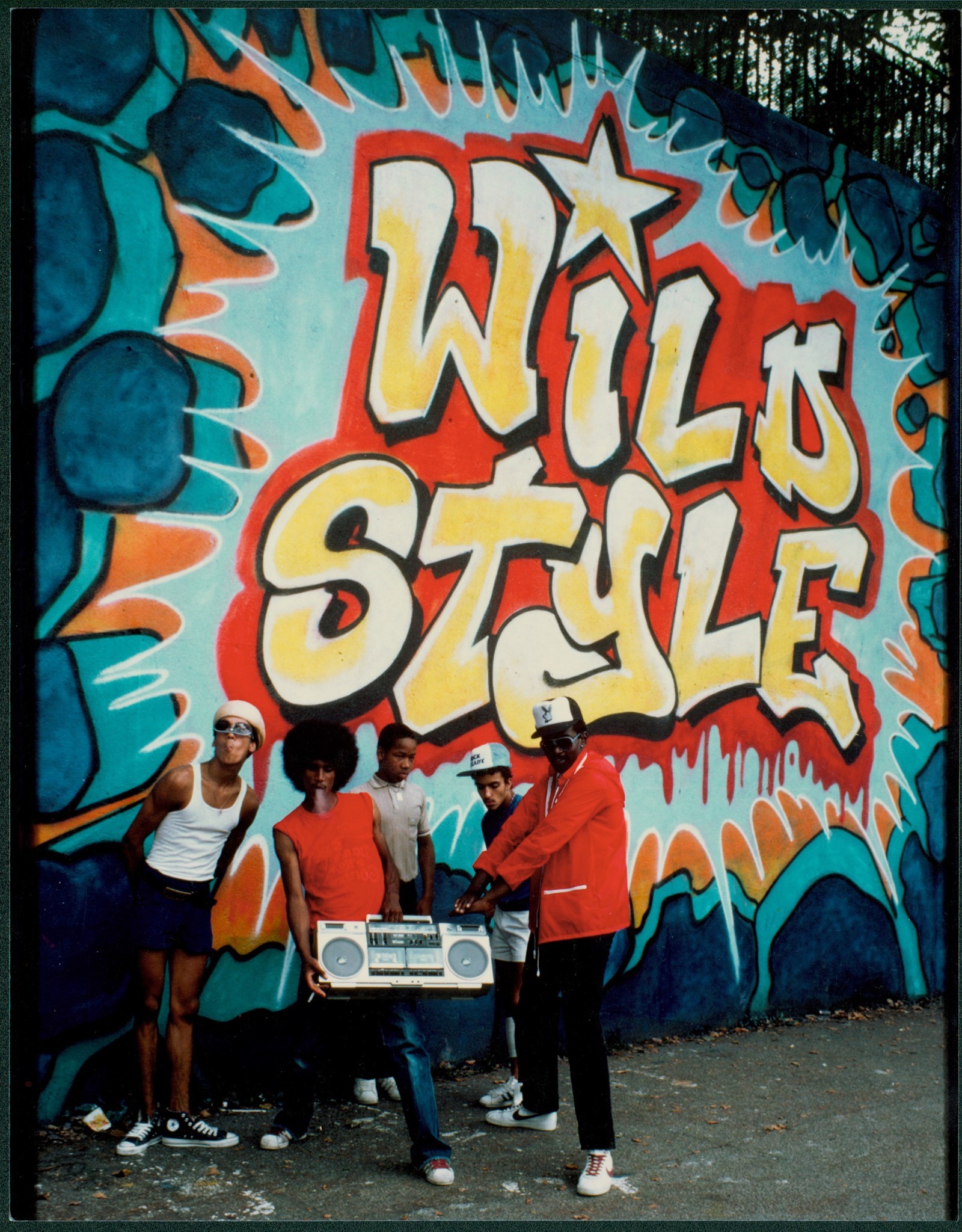

I felt like in the ways that I was being exposed to graffiti and seeing it, in its large scale, or on its massive platform— which like, you know, the trains were the canvas in New York that were moving around the Iron Worm. And, you know, these guys and girls was risking it all to be represented all over the city.

But then you seen these handball courts that had more of a permanent setting and highlighted a style that celebrated the culture. That made you feel like, when you looked at it, you knew what it was. When you posed in front of it, you probably had your arms folded, you know what I mean? A compliment to all these pieces is how many footprints you see on the wall because people were posing with it (laughs), you know?

I’ve always been turned on about knowing that Black and Brown people produced these pieces. Seeing them in the neighborhoods meant that “these were our heroes,” and I wanted to do that. Nobody is going to know who you are because you walk away from the piece. But then you get to see everybody else enjoying it. It’s gratification on another level, where I did something that everybody can enjoy. I did something that everybody could stop and take the time to look at, as if they were looking at a movie screen, you know? You get a certain energy from that and when you do it one time, it’s like a bug, you got to keep knocking it out, keep doing it. And you feel like you disciplined yourself to create something to finish. That’s what turned me on about graffiti—the urgency to put it up, walk away from it, and then watch it live.

The Nexus Excerpts are portions of the Nexus podcast conversations, with additional visual references. The text is lightly edited for brevity and clarity, but the sound of the podcast’s language is maintained. To hear more about Gibbs and his work, check out the Nexus Podcast with Rob Problak Gibbs.